Mok Chiu-Yu and Li Ching’s Letter to the Young Intellectuals of Hong Kong + Vlado Kristl’s Death to the Audience

Tuesday, May 2, 2017 at 7:30pm

Light Industry, 155 Freeman Street, Brooklyn

Presented by George Clark

“Since the traitors have taken film captive you can’t make films any more. Film is dead! There’s only one option available. You take the camera and the rest of the material, if you can get your hands on it, and just let it run. Irrespective of whether anyone is in front of the camera or behind it, or whether there’s no one there at all. If you just let the camera run and don’t try to interfere, or to influence anything in any way, then you achieve something you can call a new language…If we treat our man-made resources (the camera) with equality and allow them equal creative freedom then we will experience a corrective in our practice. Instantly everything changes in the world. The master/slave relationship which has been lurking around in our heads up to now has to be corrected.” – Vlado Kristl

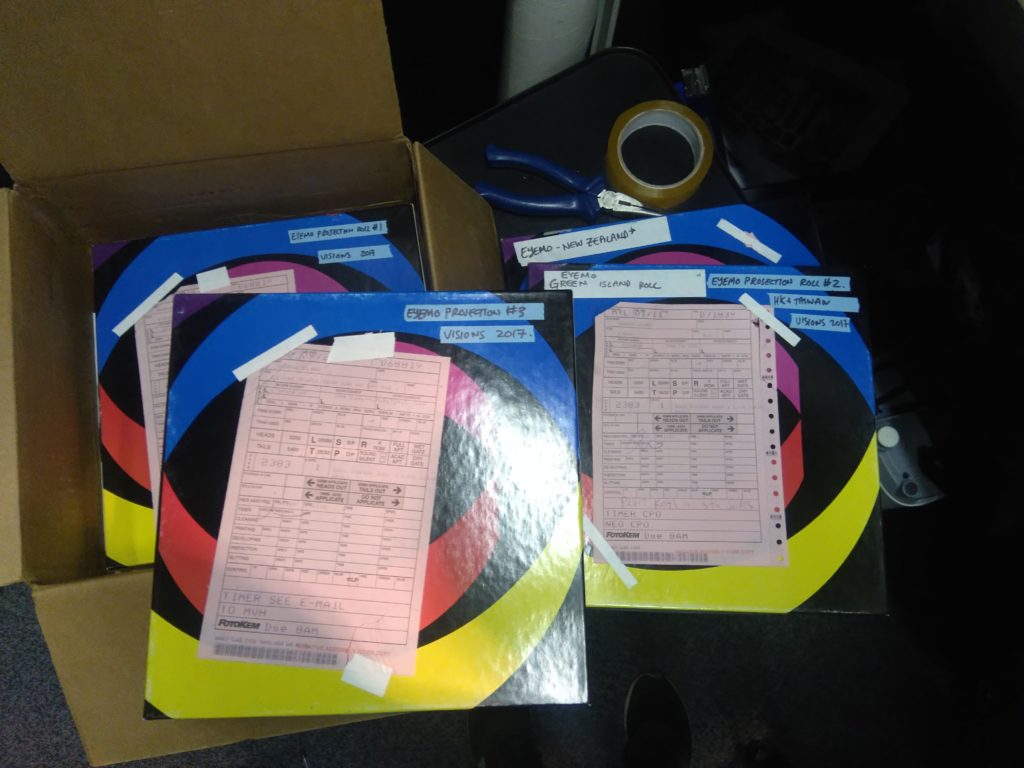

These two works are linked by their willful misuse and appropriation of elements of industrial cinema, in particular the standard gauge of 35mm. Mok Chiu-Yu’s film was shot in Hong Kong in 1978 in 35mm Cinemascope and Kristl made his 35mm film in Hamburg in 1984. I saw both pieces at archives in their original languages and became fascinated by them without knowing what was really happening. Neither director has ever had a subtitled print struck, and they only had limited visibility in their home countries. After these initial archival viewings I have since shown both publically, and find them ever richer now that I’ve been able to watch them with subtitles. But the initial opacity that so intrigued me has remained. The only extant 35mm print of Mok’s film is held at the Hong Kong Film Archive as a master element and is not loanable; Kristl’s film on the other hand was only subtitled in English following its digitization in 2014. This is the first time they are being screened together, bound perhaps by virtue of their remoteness but also, I hope, their iconoclastic approach to what it means to make a film. – GC

Letter to the Young Intellectuals of Hong Kong / 給香港的文藝青年, Mok Chiu-yu and Li Ching, 1978, 35mm Cinemascope transferred to digital, 15 mins

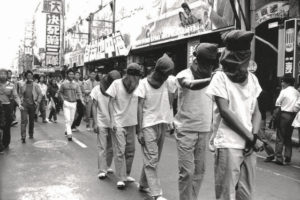

Mok Chiu-Yu is best known in Hong Kong for his work in theater and social activism, and as the co-founder of the magazine 70s Bi-weekly with Wu Zhong Xian. His Letter to the Young Intellectuals of Hong Kong, made with Li Ching, is a highly original and unique work, eschewing the production methodologies of the popular Hong Kong film industry in order to address the territory’s under-represented radical Left. The film was originally shot on Shawscope, with Mok guiding us through his hang-outs and debating the possibility of making a revolutionary film. Letter cuts and pastes aspects of commercial, personal, and experimental cinema, resulting in an invaluable record of the anti-imperialist movements in British-controlled Hong Kong. Beginning with what appear to be outtakes from a documentary about a Henry Moore exhibition at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, the film progresses through a series of aesthetic maneuvers—over-dubbing, painting directly onto the film, et al—through which Mok turns the material into an incendiary missive to Hong Kong’s youth. Intercut with newly filmed material of bohemian gatherings as well as documents of artistic interventions across the city, the piece is a subversive diary of Mok’s political activity and an idiosyncratic portrait of his generation.

Death to the Audience / Tod dem Zuschauer, Vlado Kristl, 1984, 35mm transferred to digital, 91 mins

Vlado Kristl’s Death to the Audience is a paradoxical film, a monument made from non-events. It resists artistic intention yet is marked by personal experiences of exile and anarchistic gestures. Vlado Kristl (1923–2004) was a divisive figure who was a celebrated poet, abstract painter, and filmmaker in Croatia before relocating to West Germany in the 1960s, where be produced a body of pioneering animations and experimental films, as well as performances and installations. Filming on the streets of Hamburg between parked cars, with a cast consisting of friends, students, passers-by, and a large German Shepherd, Kristl set out with Death to the Audience to challenge all expectations about making and watching a film. As he declared at the time, this is “a non-film for non-viewers.” The piece begins with a series of long takes in which the cast perpetually wait for filming to begin, which gives way to drawings and animation reflecting Kristl’s time as a refugee. Many of the strategies Kristl developed throughout his work are here combined, taken to a sublime new height; subjectivity is banished as Kristl strives to find a new equality between filmmakers and their machines.

Augustine Mok Chiu-yu was a founding member of the Asian People’s Theatre Festival Society in Hong Kong, with whom he performed and co-produced many plays. He is editor of The Revolution is Dead; Long Live the Revolution and Voices from Tiananmen Square, published by Montreal’s Black Rose Books. His other film works include Black Bird, A Living Song (1987), Cheers (1999), and Port Unknown (2008), made in collaboration with Bangladeshi theater/film artist Mamunur Rashid. He acted in Ann Hui’s film Ordinary Heroes (1999) and Evan Chan’s Life and Times of Wu Zhong Xian (2003), based on the history of political radicals in Hong Kong in the 60s and 70s. Mok has produced many plays involving artists with disabilities, was Executive Secretary of Hong Kong’s Arts with the Disabled Association, and recently organized the Hong Kong International Deaf Film Festival.

Vlado Kristl was a key participant in both the avant-garde in Yugoslavia and radical political cinema in Germany, influencing signatories of the Oberhausen Manifesto and the New German Cinema of the 60s and 70s. Kristl was a poet and founding member of the EXAT ‘51 art group in Zagreb before he turned to filmmaking, producing work at Zagreb Film Studio including Don Kihot (1961), his irreverent Cervantes adaptation, and The General (1962), the banning of which forced Kristl to flee Yugoslavia. After traveling in Italy, France, and Chile he settled in West Germany, where he made Der Damm (1966) and increasingly unruly feature films such as The Film of the Authority / Obrigkeitsfilm (1971), leading him to be celebrated by the likes of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet (who appear in Obrigkeitsfilm) and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. A contemporary of Alexeij Sagerer and Herbert Achternbusch, he produced the majority of his work in Munich, but relocated to Hamburg in the 1980s to become a sought-after if controversial teacher at the Hamburg Academy of Fine Arts (HfbK), during which time he made Tod dem Zuschauer. Throughout his career he wrote, designed, and published a highly original series of artist books featuring his poems, drawings, aphorisms, and scripts for unmade and unmakeable films.

Digital version of Letter to the Young Intellectuals of Hong Kong courtesy of Mok Chiu-Yu. Thanks to Thomas Beard and Ed Halter.